home

home |

Home Planning Maps FAQ Library Gallery Press Rentals Calendar Donate |

Gorse, Glyphosate, and Greed |

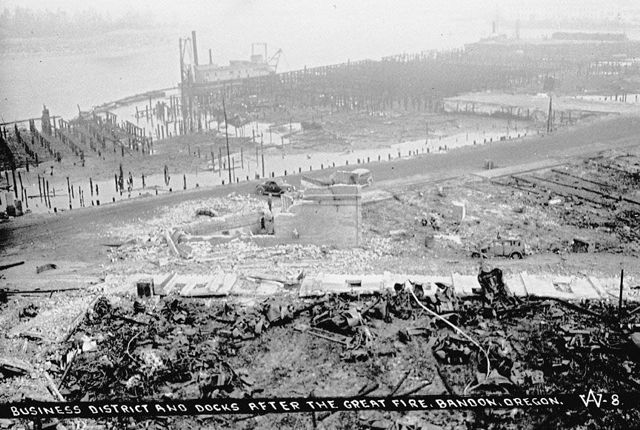

While grubbing out a firmly rooted Gorse plant on our Headlands, I was thinking about some of the more ironic facts of human life. Gorse, aka furze and Ulex europaeus, would not be here if not for another alien life form, namely: us. Local legend says that a Scots dairy farmer, having achieved some prosperity in Caspar, traveled to the Auld Country and saw the miraculous hedgerows of evergreen thorny bushes with bright yellow flowers even in the dead of winter. On stony Scottish soil, sheep and cattle keep Gorse confined to hedgerows between fields. Our early Casparado clipped some starts, wrapped them in a napkin, tucked them into his luggage, and brought them home to plant in place of those pesky barbed wire fences that were always falling down. What could possibly go wrong? When his little gorse clippings encountered the richer soil and balmier Caspar climate, they took off. No herd of cattle or sheep had a chance of confining Gorse to the edges of our fertile, clement fields. Over the years, many methods of controlling gorse have been tried, and most have failed. The biological control often seen here, the Gorse Spider Mite Tetranychus lintearius, another European native and one of Gorse's ten known predators, is smart enough not to completely eliminate its only food source. Gorse itself is unbelievably hardy, enthusiastically regenerating itself from seed, branch, or root. Heavy equipment used in abatement efforts must be carefully steam cleaned after use, or seeds and twigs on it will start an infestation wherever the equipment next works (hence the infestation at Caspar Dump.) Cutting Gorse's tops merely encourages stronger root systems on the resurgent plants. Branches, stems, and roots contain 30% or more of flammable oil, and Gorse thrives on fire, shooting its thousands of fire-resistant seeds 30 feet; these seeds have a half life of 30 years, meaning that at the end of three decades, half of the seeds are still good to grow. Gorse is one of Caspar's nightmares. In 1987, a fire started in a Gorse patch on the north side of town. Because the roots are as oily as the stems, Gorse burns underground. The fire was stopped before it took houses ... that time. With ongoing drought and the Valley Fire on everyone's mind, Gorse abatement resurfaces as one of Caspar's hottest topics. In 1999, the Caspar Community identified Gorse and Eucalyptus as two of our most dangerous neighbors. Since then, much of the Eucalyptus has been removed, and many of the worst Gorse patches have been attacked, with some success. The fact remains that one Gorse bush is too many. While newcomers admire its cheery yellow blossoms during the darkest days of February, we know that its forbidding spikes and stubborn persistence are best confined to its native Western Europe. The Mendocino Fire Safe Council, whose mission is “to help the citizens of Mendocino County survive and thrive in a fire-prone environment” has a Caspar contingent who help property owners get funding to attack their Gorse infestations. The abatement conundrum with a plant as stubborn as Gorse is that once planted, it takes almost super-human persistence to wipe it out. Chop its top, and it comes back with strengthened roots. Introduce Spider Mites, and up to half the Gorse crop will be set back a year or two at most. Mow it for a few years, and your reward is a “lawn” of ground-hugging Gorse. Burn it, and it spews seeds that resprout in a year. Uproot it, and inevitably it regrows from little bits of root that break off and remain in the soil. Stuart Tregoning and Ralph Eagle developed a technique involving mowing, ripping the soil up to expose the roots, and then following up annually without fail by pulling up the shallow rooted sprouts ...but skip a year, and you get to start all over again. State Parks has invested a great deal of money in first-year abatement, but without perpetual follow-up, the Gorse regrows. Caspar Community has had the greatest success of any (although the maintenance effort continues) on our Headlands, where uprooting and stacking the plants with the roots exposed has decreased the Gorse coverage by half.  Bandon, Oregon, after the Great Gorse Fire of 1936 Gorse isn't just a local plague. Other farmers imported it unknowingly to Australia, Hawaii, Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Scandinavia, even to some subarctic islands. Gorse was the principal cause of a fire that destroyed Bandon, Oregon, in 1936. What's wanted, of course, is a silver bullet, something as simple and sure to end gorse as thrusting a gorse clipping into the ground is sure to start an infestation. The good news and bad news rolled up in one is that such a silver bullet exists ...and so far, Casparados choose not to use it: Cut the gorse stem at ground level and immediately, carefully, paint it with the herbicide glyphosate, and that Gorse plant is done. A crew with good loppers, a chain saw, a pint of chemical, and a carefully wielded paint brush can finish off an acre of Gorse in a day. True, all the cuttings need to be dealt with, and the existing seed stock will be viable for a few decades; annual grubbing up of the sprouts will be absolutely required. But most of the heavy work will be done once ... and the followup can be carried on by livestock as picky as horses, who appear to love the tender little Gorse seedlings.

Here's where the tale gets really twisted and interesting. You may know glyphosate by its proprietary name, RoundUp, and disparage it because of its corporate parent, Monsanto. Gorse and Monsanto have a lot in common. Their goal is to dominate as much territory as possible. Greedy and utterly devoid of human ethical considerations, they are willing, nay, eager, to use underhanded means to achieve their goals: Gorse employs chemical warfare (allelopathy), dispersing a toxic oil on the soil beneath it that poisons every other growing plant. Monsanto uses lawyers. Where Gorse may be held responsible for burning down small cities, Monsanto is responsible for demonizing Genetically Modified Organisms, thereby compromising a technology that could, if ethically pursued, mitigate global hunger and malnutrition. While you may join me in hating Monsanto, it's worth remembering that we, too, are invasives. Had George Bennett, the founder of Bandon, not also been the culprit who imported Irish Gorse, the city would still have its pretty pre-1936 downtown. Nobody is willing to admit their family brought Gorse to Caspar – scions of the two likeliest families point fingers at each other – but some non-native immigrant did. Every time we bring home an exotic plant, we run the risk of loosing a plague. That's how Eucalyptus, Himalaya Blackberry, Monterey Cypress, Vinca, Pampas Grass, and a long list of other invasive exotic plants got here ... and so that is certainly an important part of our story: if we are to become successfully naturalized within our environment, we have to be very, very thoughtful about who we invite to our garden parties.

But the main theme of this piece is Gorse, and what we are willing to do to rid ourselves of it. If I could accomplish one thing in my lifetime and feel my life had been productive, it would be to completely remove the threat of Gorse from Caspar. I am as passionate about that as was George Bennett about finding an easy way to grow fences around his Bandon holdings. While I deplore Monsanto's business model – developing trademarked life-forms that are resistant to poisons that make it possible for sloppy industrialized agricultural practices to wrest maximum short-term profits from the soil, and sue anyone who says them Nay – I am not afraid of glyphosate. Monsanto's last trademark expired in 2000, and companies besides Monsanto make it, so confusing the Gorse Abatement conversation with references to Monsanto isn't useful. I'm an old and careful fellow, and I'll cheerfully assume the health risk of applying the chemical to the cut stems. As long as I can get down on my hands and knees to pull up Gorse seedlings, I'll go out onto our patch, the Caspar Headlands, and pull up seedlings (since State Parks rightly won't let us use goats or horses.) So why don't we just do it already? There might be two basic reasons, but the over-riding reason is that Caspar is a community that works by consensus. We acknowledge and honor the nay-sayers, the one (or two) firm, idealistic voices that say, “Let's not support Monsanto. Let's not take any risks with herbicides.” Those with broader experience in the battle to abate exotic infestations have told us, “Without chemicals, you will never get rid of Gorse.” They told us the same thing about Eucalyptus, and, after eight years, we have nearly proved them wrong. I disagree with those idealistic voices, but I honor them in their firmness. So every fourth Saturday finds me, and a doughty crew, out on the Caspar Headlands ripping out Gorse plants ... and heather, and broom, and thistle, and the Eucalyptus stragglers. Join us. There's plenty of work to do. And afterwards, we eat lunch together. originally published in the October 2015 Caspar Community News

page updated 31 October 2015 mrp |

|

Home Planning Maps FAQ Library Gallery Press Rentals Calendar Donate |

|

Caspar Community Center 15051 Caspar Road Caspar, California 95420 - box 84 707-964-4997 | |

|

If you would like to receive email about hometown Caspar events, email your request to lists@casparcommons.org. | |

|

find Caspar Community Center on: |

|

| Community web hosting donated by Mendocino Community Network Thank you, MCN! for more information, email the Caspar Community Coordinator, caspar@mcn.org |

| copyright © 2024 Caspar Community permission to reprint is hereby granted and EARNESTLY desired |

|

: : last updated 29 April 2019 : 12 pm (s) : : printed with 100% recycled electrons! for website feedback, email the Caspar Village webster |